By Shweta Bhandral

The news of young children committing suicide is the most tragic and traumatic to hear as a parent. Mental-health issues are deepening in our society, and no one is asking the right questions. In the recent case of three young sisters committing suicide in Ghaziabad, a familiar and deeply troubling pattern has emerged.

Instead of asking difficult questions about loneliness, isolation, parenting, or the digital lives of our children, parts of the media have chosen an easier villain: Korean content.

As a parent, journalist and guidance counsellor, I find this narrative not only inaccurate, but dangerous. I did not begin watching Korean dramas out of curiosity or fandom. My daughter, who is 16, likes them.

So, over the past six months, I have watched more than 25 K-drama shows along with her, and I say this without exaggeration: I am thankful my child is watching this content instead of much of what currently dominates Indian OTT platforms.

This gratitude comes from observation, not blind admiration.

In my opinion, K-dramas are emotional, easy to watch and culturally safe. They do not rely on shock, profanity, excessive violence or sexual aggression to keep viewers engaged. There is more emphasis on storytelling, silence, empathy and human connection.

I don’t mean that Korean society is free of problems. They have their own issues, which reflects in their shows. The society is patriarchal; you will also see class disparity, corruption and gender stereotypes. Drinking culture is casually promoted and presented as a normal part of adulthood. Hierarchy matters in relationships, so much so that the language style differs when they speak with someone their age versus when they speak to elders. This is visible in almost all their dramas.

Having said that, the greatest strength of Korean storytelling is its subtlety in dealing with complex themes. Without preaching or sensationalism, they address larger issues. For example, bullying in schools is tackled in almost all dramas that deal with teenage romance. Shows like Summer Strike, True Beauty, The Glory, and many more, highlight school bullying truthfully, creating awareness and empathy.

Economic inequality, class shame and stereotypes are visible in dramas like Hometown Cha Cha Cha, King the Land, The Typhoon Family and others. Issues like competition for higher education and the importance of money are highlighted in dramas like Sky Castle and Crash Course in Romance.

Mental health, burnout, grief, love, parenting, relationship issues, patriarchy and loneliness are tackled in almost all shows. In One Spring Night, three sisters deal with a difficult father, domestic violence and misogyny, yet everything in the series is woven beautifully with a supportive mother and a male lead who together empower the sisters.

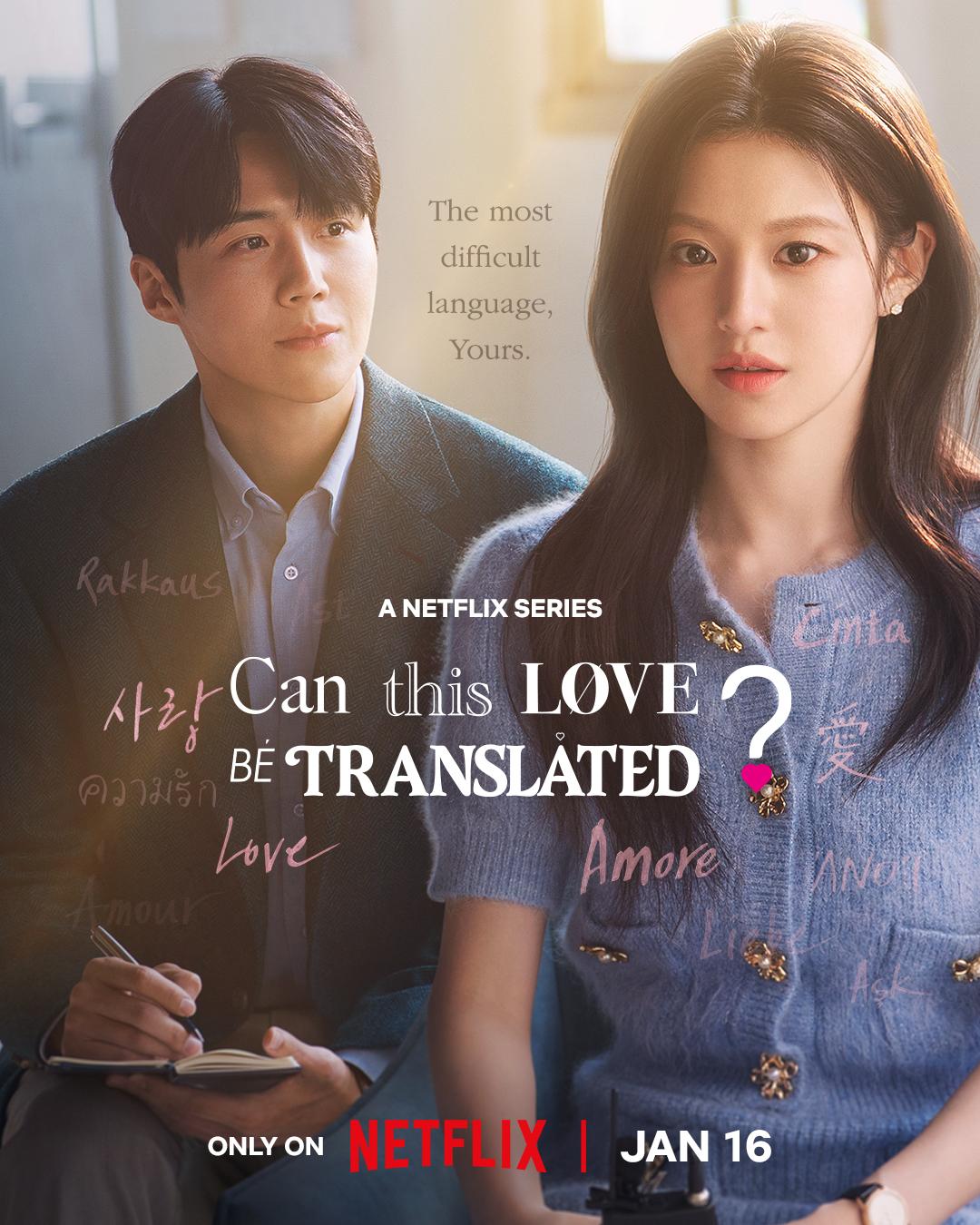

Something in the Rain deals with hyper parents, sexual harassment in the workplace, and a psycho ex-boyfriend, yet the series leaves you with hope and love. The newer shows like When Life Gives You Tangerines and Can This Love Be Translated? take empathy to another level.

In one scene in Can This Love Be Translated?, the male protagonist and his writer uncle talk about how each one of us have our own language and we should try and understand the other by reading them as a whole, not just with their words or silences.

These shows and others I have watched handle social issues with resilience and understanding, not with aggression and violence. These themes are woven into the everyday life of the protagonists, not screamed through graphic trauma. This makes them accessible to young viewers – and, I would say, more impactful.

That’s probably why K-drama culture feels threatening to Indian society. The real discomfort is ideological.

K-dramas promote an equitable society rooted in respect and kindness. They encourage slowing down, noticing nature, valuing routine, respecting elders and choosing kindness even when life is unfair. They soften authority and humanise everyone. This unsettles societies built on high control and rigid stratification – like ours.

Indian boys and men should watch K-dramas precisely because they present a version of masculinity that is calm, respectful, emotionally intelligent and nonviolent. Male characters express vulnerability without ridicule; their heroes treat women as fellow human beings and resolve conflict without domination.

K-dramas do not sexualise bodies. They do not use the camera to objectify women. In a society like ours, where popular media often normalises entitlement, aggression and casual misogyny, this alternative representation matters.

I also noticed something unexpected: these shows are calming. They reduce anxiety rather than heighten it. India’s OTT industry has grown rapidly, but its most visible content is dark. It has increasingly leaned on profanity, gratuitous violence and unnecessary sexual scenes, often derogatory to women and framed as realism, from the latest ones like Daldal to the older ones like Mirzapur and a lot in between.

Against this backdrop, Korean dramas feel almost radical in their decency!

It’s no wonder why Korean content’s share on Netflix grew from 2 percent in 2020 to about 6.8 percent in 2024, making it the third most prevalent language after English and Spanish.

The narrative woven by the media in the wake of the Ghaziabad tragedy is that Korean fascination resulted in the suicide of three young girls. This framing is not only irresponsible, but it is also a profound failure of public reasoning.

Reports point to the sisters’ long-term isolation, withdrawal from school, excessive unsupervised screen time, domestic violence, and emotional disconnect within the family. These are known risk factors for adolescent mental distress worldwide.

Content does not cause suicide. Isolation does. Silence does. Lack of emotional support does. Mental-health outcomes are shaped by complex social, familial and psychological factors, not a genre of entertainment!

Responsible media consumption for children requires media literacy, parental engagement and emotional support, not a narrative that simply points a finger at someone else.

Instead of blaming what our children are watching, we should ask what they are missing – and what kind of world we are preparing them for.

Shweta Khanna Bhandral is a career counsellor, communication skill coach, media literacy trainer and visual storytelling expert. With 26 years of work experience as a journalist and educator, she now runs FutSki Labs – The Future Skills Company, which offers career guidance and courses in focus building and communication skills.

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The article is presented beautifully and articulates a real societal issue with clarity and precision. There is a need for a change in mindset. And further work is required in this direction.

LikeLike

Very well put across. I totally agree with you Shweta. Parental engage and emotional support can overcome any turmoil within.

LikeLike