By Sapphire Mahmood Ahmed

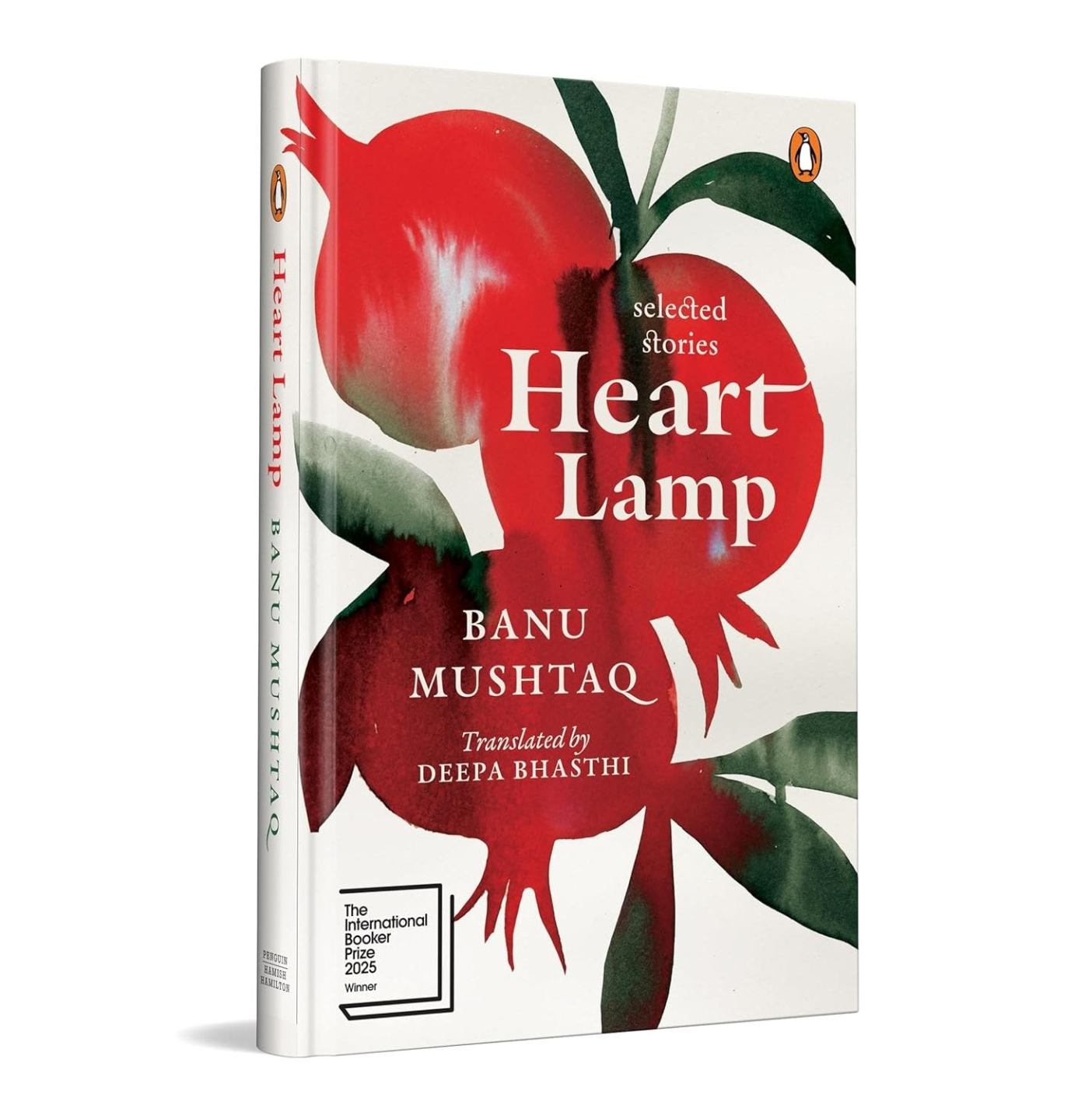

Literature has always been full of tired women, even if their tiredness is rarely named. In Banu Mushtaq’s ‘Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal’ from her short-story collection Heart Lamp (2025), which won the International Booker Prize 2025, the house called Shaista Mahal is filled with affection, with flowers in the garden and easy talk of love from the husband, but it is also a place where labour never quite stops.

Shaista Bhabhi moves from one pregnancy to the next, her body carrying the rhythm of the household, while her eldest daughter Asifa slips out of school and into care work, tending to siblings and responsibilities that arrive far too early.

Nothing here looks like a crisis. This is ordinary life, arranged to keep going. What the story makes visible is the absence of pause from a world in which care accumulates without interruption. Here, rest does not appear as something one can claim.

In recent years, exhaustion has entered public conversation, often spoken of in terms of burnout, wellness and recovery. Yet this language often assumes that rest is available once it is deserved or diagnosed. Ordinary fatigue, especially when it does not interrupt productivity, remains largely unremarked.

This gap between how much exhaustion is acknowledged and how much is quietly absorbed reshapes how we might return to older feminist arguments about space, rest and thought. It is here that Virginia Woolf’s famous insistence on a room of one’s own begins to feel both necessary and incomplete. Woolf understood that women needed space, money and privacy in order to think and create.

Woolf’s room, after all, is built on the assumption that uninterrupted thought is even possible. That there are women who can close a door, sit with a sentence, and follow an idea to its end without being pulled away.

But literature also reminds us that many women never reach that threshold at all. Not because they lack talent or desire, but because their lives are organised to be endlessly interruptible. Like Asifa, whose days are shaped by others’ needs long before her own can take form, thought itself becomes a luxury. It is something that must be abandoned midway, returned to later, or learnt to do in fragments.

What if the room does not arrive at the beginning of a woman’s life, or even in its middle? What if it becomes available only after collapse, after the body refuses to go on, after endurance finally fails? In such cases, rest is an aftermath. A concession. Something granted only when productivity has already broken down.

Rest, the right to step back, is unevenly granted. A woman who stops is expected to justify herself, either through illness, breakdown or failure, while endurance is praised as long as it remains functional.

This ‘room’ is further distanced by modern economic shifts. While the Economic Survey 2025-26 celebrates a rise in women’s workforce participation, it simultaneously warns of the ‘imbalance’ in domestic responsibilities.

In 2026, the modern Asifa isn’t just slipping out of school. She is the woman managing a gig-economy job while her unpaid labour at home remains a ‘staggering’ five-hour daily debt that men rarely share. We talk about the ‘Care Economy’ in policy papers, yet we still treat the individual woman’s exhaustion as a private failure of management rather than a public crisis of erosion.

The line that marks when a person is allowed to stop to rest, withdraw or step back is not drawn at the same place for everyone. This is where privilege begins to show. For some, the line is close. Fatigue is recognised early. A pause does not threaten the stability of the world around them. When they stop, something else holds.

For many others, the line is placed much farther away. They are expected to keep going past ordinary tiredness, past warning signs. Their exhaustion must first become visible enough – through illness, collapse or failure – before it is believed.

And for some, the line is drawn so far that reaching it would mean leaving others unheld. Their stopping would create a vacuum no one is prepared to fill.

Many women, like Asifa, stand precisely at this distance. Her tiredness is irrelevant. Her usefulness is not. Long before she reaches the point of collapse, the line has already been drawn ahead of her, marking how far she must go before rest can even be imagined.

It is tempting to think of exhaustion as something that arrives in dramatic moments, like a breakdown, a burnout or a visible refusal. But much of women’s exhaustion does not look like collapse. It looks like erosion. Slow, cumulative, almost imperceptible. Like rock worn into soil, not by a single catastrophe but by years of small, unremarkable pressures.

Asifa does not break spectacularly. She is worn down into usefulness, shaped by expectation into a surface on which others can live. Erosion is quiet. It does not demand witnesses. It does not interrupt the household, the family, the story of love and care that continues around it. This is the privilege of some lives over others: some people are allowed to be rocks, solid and uninterrupted, while others are quietly transformed into ground.

Asifa does not collapse in Mushtaq’s story. She does not refuse, rage or fall apart. She simply adjusts, slipping into the work that needs doing, learning early how to carry what others will not. Her life is not marked by a dramatic breaking point, but by a gradual narrowing. This is how erosion works: not through spectacle, but through repetition.

We are often taught to look for physical collapse as evidence of harm. But erosion leaves no such proof. It produces continuity. The household runs. Care is provided. Love continues to be named. And so, the cost remains easy to ignore. Privilege operates precisely here, in who gets to break and be recognised, and who must be worn down quietly so that everything else can hold its shape.

An analysis of privilege often makes people uneasy because it is difficult to locate. It does not accuse individuals so much as it rearranges the frame. It asks us to see how ordinary arrangements, like love, care, family, responsibility are sustained by unequal distances.

This kind of analysis is unsettling precisely because it does not offer a clear villain, nor an easy point of refusal. It implicates structures we inhabit and benefit from, sometimes without intention, sometimes even with affection.

Stories like Asifa’s matter, even when they refuse drama. Her story does not ask for resolution. It does not offer transformation or release. It asks only to be seen as a record of how erosion is mistaken for virtue, and how the absence of collapse is too easily read as the absence of harm.

Dr Sapphire Mahmood Ahmed is a researcher, academic and writer whose work focuses on gender, culture and women’s everyday experiences in Kerala. She teaches literature and researches digital narratives, emotional labour and identity.

Photos: Sujay Govindaraj

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “Labour, fatigue and the unequal privilege to rest in ordinary Indian households”