By Neha Kirpal

As the first woman to start working as a naturalist at the Ken River Lodge at Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, Ambalika Singh Rathore has had a wild ride in many ways.

“I mean, just imagine driving around the jungle every day, tracking the big cats, birds and all the animals in and around as an everyday job? It’s definitely my dream!” smiles the 28-year-old, who co-founded Shikra Wildlife Expeditions, which takes people on guided tours customised according to their ideas and interests.

Ambalika had always been an outdoor person since childhood. Her father was in service with the Border Security Force and retired as an Inspector General last year. As a family, they were constantly travelling across the country, including to many remote places close to national borders.

She grew accustomed to a variety of natural habitats from the snow-covered valleys and peaks in Kashmir, lush evergreen forests in Sikkim, pine forests in Shillong, the unique mangrove forest in Malda, West Bengal, to the desert in Bikaner and the infinite salt lakes of Kutch.

These were locations that were very sensitive in terms of their proximity to the national borders, and were also mostly untouched by civilisation. Ambalika explored what she could, always surrounded by animals throughout her life as if she had some sort of unbreakable bond with them.

“I was exposed to all sorts of terrains and connected with each of them. Every place was way different and had a character of its own, and I got the time and resources to explore these places to the fullest,” she recalls.

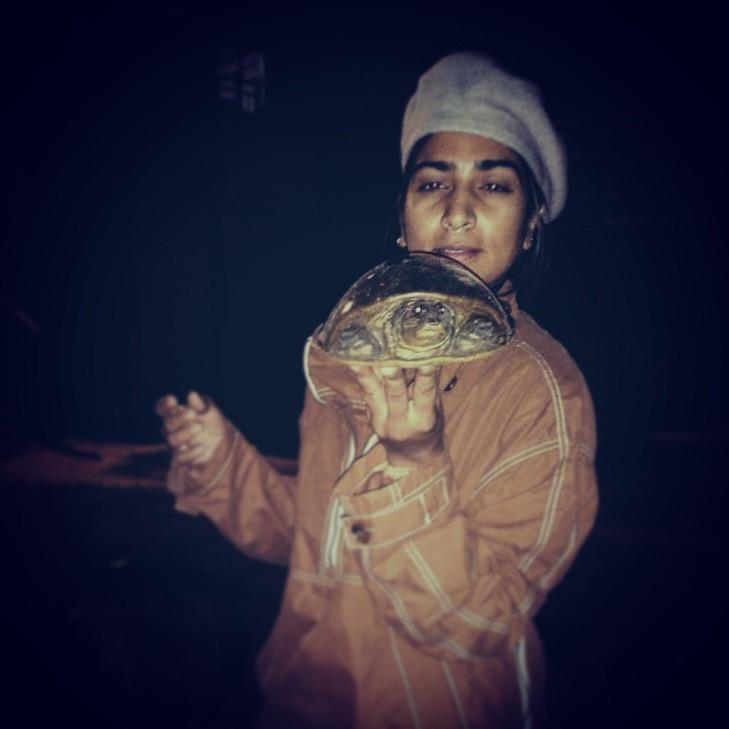

As a child, she devoured books and television shows like Animal Planet and National Geographic. “I was never scared of surrounding myself with animals or even handling critters like lizards and snakes,” she says.

Ambalika completed her Master’s in industrial psychology in 2017 after which she worked with the Government of Gujarat and the Indian Institute of Public Health on a mental-health project with soldiers on field until 2019.

That’s when she met her husband, Parikshit, who was working as a naturalist for Ken River Lodge, Panna. He introduced her to the idea that wildlife as a passion could be pursued as a profession, and she jumped headfirst into it. She joined as a naturalist at Ken River Lodge as the first female naturalist of the lodge.

It was something that took a lot of convincing for her family to agree on, but it was the only time when she put her foot down. “The job felt perfect for me and I found my happiness while also managing to find a source of income to sustain myself!” she exclaims.

It is a niche that has been predominantly occupied by men. Just 13 percent of the guides at the Panna National Park are women, most of whom have only been recruited since last year as an initiative of the Forest Department.

This concept was something alien for the male drivers and guides of the reserve, more so when Ambalika started taking guests out for drives within the national park back in 2019.

“There’s a lot of stigma attached to women driving. And a woman managing a Gypsy within the park and driving through rough terrain — while tracking animals simultaneously — was very difficult for them to digest,” she says.

Initially, when she started driving in the park, the driver heading towards her from the opposite side would swerve his vehicle off the road completely as if trying to save it from getting bumped. Rumours circulated that Ambalika used to crash into other vehicles, which had actually never happened. Ambalika would brush these off, and look at them from a humorous lens.

“If nothing, I was happy that they were scared of my approaching vehicle; it made the drives easier for me! I knew they would come around, which they eventually did. I believe I’ve proved myself efficient as a naturalist, a guide and a driver. The parameter of my success is that I’ve managed to garner mutual respect and affection of my male peers,” she enthuses. “I’m not an outsider anymore, I’m one of them now. It’s not just their world anymore, it’s mine too.”

In her fourth season working out in the wild, Ambalika has seen tigers and leopards umpteen times. “Yet a shiver runs down my spine every time I spot one,” she beams. She now sees things from a different perspective, compared to when she started out.

“It’s an everyday learning. I had to unlearn and relearn everything, keeping in mind the context that I would now have to share my knowledge with the people I meet. And this knowledge had to be impeccable,” she explains.

Being on the field challenged the theories Ambalika was familiar with. For instance, she observed that each tiger has its own unique personality. “Be it the way they moved around in their territory, or taking your best bet on the path they would show up on, spotting pug marks and listening to the jungle calls. All of this had to be done simultaneously and sensitively,” she says.

Gradually, she got better at reading the signs of the forest with more depth, like the tiger marking its territory, how the cubs are raised, or what is their mood and pace for the day.

She draws inspiration largely from her husband, and also from the women in his family. “I have been very lucky to get married into a family that always put the needs of women first. Never have I been questioned on my work life. Instead, I have always only received all their support. The ladies in my family are all very headstrong and independent women in their own thought process and fields,” she says.

Talking about the role of women in forests and wildlife conservation, Ambalika shares that women have been at the forefront of many forest and wildlife conservation movements, dating back to the story of Bishnoi women protecting the Kheri trees in a village in Rajasthan in 1731.

Many other movements like the Chipko movement in Uttarakhand, Apiko Andolan in Karnataka, the Silent Valley protests in Kerala, and Narmada Bachao Andolan have seen very strong women leadership, which only goes to show the close relationship women have shared with wildlife and forests.

“Today, when deforestation and wildlife depletion is happening at an alarmingly high rate, it is essential to increase the amount of female participation in the scope of conservation. Without their active participation, the probability to conserve will be negligible,” she avers.

However, the efforts of women have not received as much recognition as they deserve. “Women have been running it all at the grassroot level but the impact goes all the way up. It’s only fair to give them recognition on a broader platform and at the macro level,” she says.

According to Ambalika, this is a field that has so much space yet to be explored. “We call nature our mother. How is it fair that most of this dominion of being a naturalist is occupied by men?” she questions.

In fact, she believes that women may be better at nature conservation work due to their innate sensitivity and communication skills. “As a woman, you have more power to be in tune with nature. It might seem intense from the outside, scary even, to be in the wild, but it is actually one of the safest places to work, because you are surrounded by people whose profession is based on respecting and communicating with nature. It’s definitely not a smooth ride, but it’s adventurous and fulfilling,” she says.

The adoration and astonishment Ambalika evokes from everyone who sees her driving around and working in the jungle inspires her and gives her a feeling of freedom and power unlike anything else.

“When Parikshit and I have kids, we have decided to homeschool them while staying in the jungles. I am absolutely convinced that it’s one of the best ways of learning,” she smiles.

Read also: How a Women’s Group in Uttarakhand Saved Their Village from Forest Fires

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Commendable effort by a young girl. To make a healthy balance of work life and traditional home is an achievement. The narrative is captured very interestingly by Neha. Great work. Dig up more such inspiring stories to encourage the women of our country.

LikeLike