By Shailaja Rao

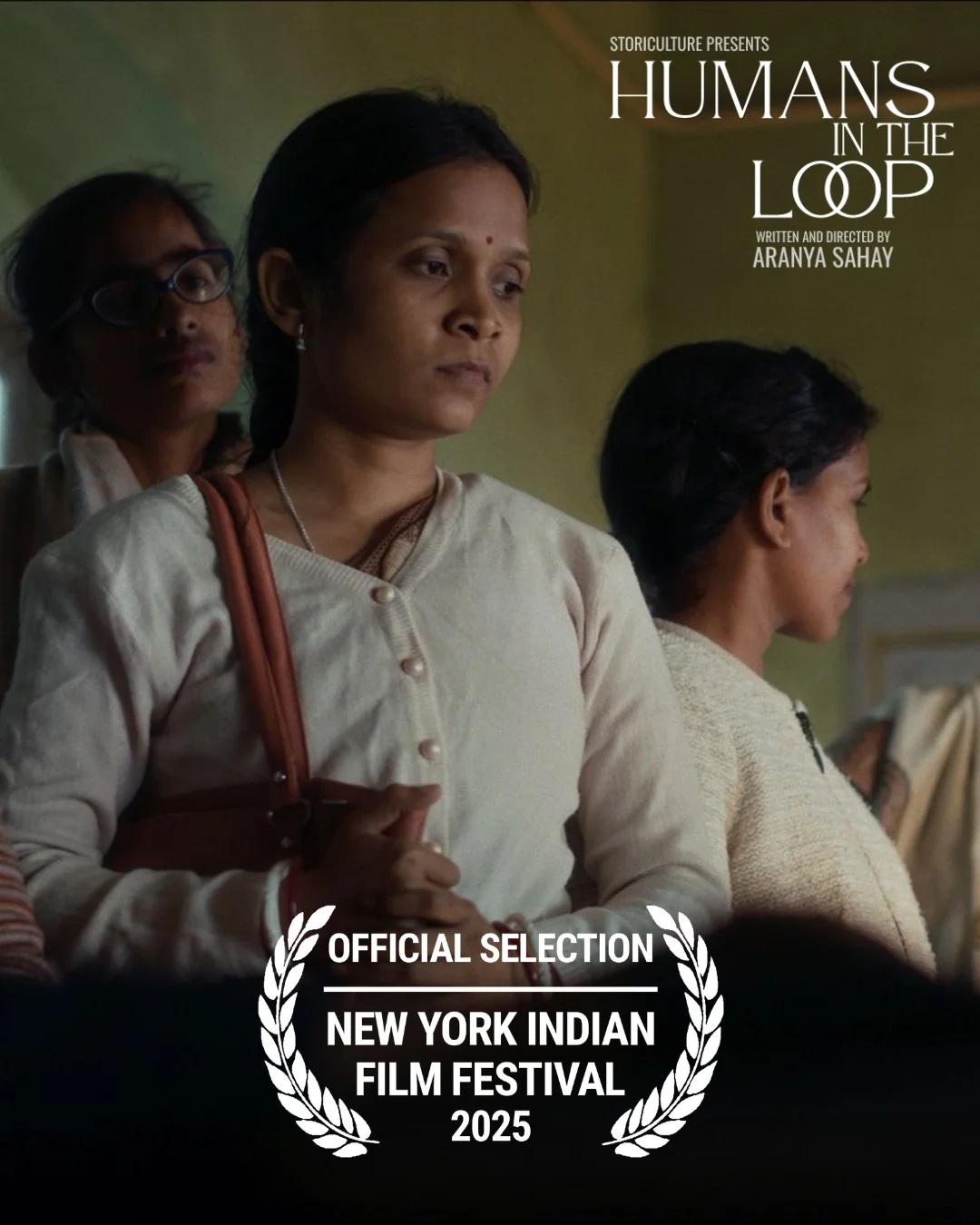

Many Adivasi and Dalit women label the data that trains today’s artificial intelligence (AI) systems, yet most of us don’t know they exist. In the new feature film Humans in the Loop (Netflix, 2025), actor Sonal Madhushankar’s nuanced portrayal of Nehma finally brings them into focus. After watching the film, I found myself wanting to learn more about the women whose invisible labour gives machines their “intelligence”.

This fictional story rests on a real and hidden workforce. Researcher Ishika Ranjan, who studies gender and migration in India’s informal sector, notes that the bulk of data-labelling labour originates from rural regions and smaller towns in India.

Many are first-generation workers, primarily women, including tribal and Dalit women who manually annotate images and objects for machine learning. Yet their identities remain absent from mainstream conversations about technology, and they remain ignorant of the realities of “algorithmic colonialism”.

Director Aranya Sahay, trained at Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), uses a fictional narrative with documentary sensibilities to humanize a technical world and explore this hidden labour.

Rather than presenting statistics or exposé-style footage, Sahay lets viewers inhabit one woman’s struggle: Nehma, a young mother at risk of losing custody of her children, returns to her ancestral village in Jharkhand and finds work at an all-women AI data-labelling center.

Through her story, the film quietly unpacks the biases and blind spots embedded in data labelling, widening its emotional reach beyond abstract concerns about technology.

Finding Nehma

For Madhushankar, the role resonated with her own identity. “Nehma belongs to a tribal community, while I am Dalit,” she tells me. “I could relate deeply to her character and to the discrimination and hesitation she experiences.”

A week before the shoot, Madhushankar visited Jharkhand and spent time with women from the tribal community. “Our conversations were heartfelt, not conducted as a formal exercise. In those moments, my only role was to listen to them, not as case studies, but as human beings,” she recalls.

She met Tarini, a widowed woman from the Lohara tribal community who was caring for three children and her in-laws in Sarugarhi village. “I did not interview her; I simply sat beside her. Her silence spoke more powerfully than words ever could.”

This approach to character building reflects a deeper truth about representation. Authentic portrayals emerge not from observation alone, but from genuine connection and surrender to another’s lived experience.

The film has won the prestigious Film Independent Sloan Distribution Grant and is now eligible for Academy Awards consideration. The grant, from Film Independent and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, supports science- and technology-themed narrative features. The film’s power lies in bringing this erased labour and the knowledge embedded within it into vivid focus.

Local knowledge meets global technology

When Nehma begins work at the labelling centre, her familiarity with the plant and animal habitats quickly becomes indispensable. During a debate about whether an image shows ginger or turmeric, her intervention with her supervisor, Alka (played with warmth by Geeta Guha), and the other workers is gentle yet firm: “Woh haldi hai. Adrak mein chhota chhota bulb nikalta hai. Haldi mein nahin.” (“It’s turmeric. Ginger grows small bulbs. Turmeric doesn’t.”)

In another sequence, Nehma sees a video of caterpillars being destroyed after an AI system flags them as pests. She explains to her supervisor that they are not pests since caterpillars only consume the rotting parts of plants, but her knowledge is disregarded due to business compulsions.

This scene, Madhushankar explains, was directly influenced by research into how tribal women relate to their environment, with a deep and intuitive ecological knowledge. Understanding this relationship helped her bring authenticity to Nehma’s portrayal – “her care for the land, her attentiveness, and her quiet, grounded presence.”

Moments like these illustrate that AI systems are only as accurate as the cultural and ecological knowledge fed into their training. Without annotators like Nehma, who carry a generational understanding of their environments, AI risks replicating misclassifications and flattening nuance into error-filled data points.

The film subtly shows that “expertise” in AI does not always come from coders in urban tech hubs; it emerges equally from the lived experiences of those labelling the data.

A poignant parallel

One of the film’s most elegant sequences unfolds during a training session on skeletal labelling. Alka demonstrates how annotating the motion of human limbs will allow a robotic figure to stand, walk and run.

The film then cuts to Nehma’s baby son, Guntu, lying in a cloth cradle suspended from the ceiling, kicking his legs with the same tentative motion as the AI figure struggling to find balance. Soon after, Guntu stands using a wall for support and takes his first steps.

Later, Nehma completes her day’s annotation and hands over her drive. Alka feeds the data into the AI system, and they watch as the robotic figure stands upright for the first time. Nehma’s expression, quiet pride mixed with awe, suggests she is witnessing something come alive, something she has helped create.

This parallel is profound. The AI figure ‘learns’ to walk through the meticulous work of women teaching it how movement looks and unfolds. Sahay’s juxtaposition collapses the distance between human and machine to underscore a truth rarely acknowledged in mainstream tech narratives: behind every algorithm is a human hand guiding its earliest steps.

Female solidarity

In one revealing moment, Alka suggests generating an AI portrait of Nehma. She types the prompt: ‘Nehma – Beautiful Tribal Woman from Jharkhand’. What appears on screen shocks them both. The AI-generated images bear no resemblance to Nehma or to any woman from the region.

Nehma’s response is simple and powerful: she decides to correct the model. Using videos and photographs of the region captured on her daughter’s phone, she feeds authentic material into the system.

Madhushankar sees this act of correction as transformative for her character. “In that moment, she’s not just doing a job, she’s parenting the AI. She’s rooting it in her own culture, challenging the narrow boxes it’s being trained in, and demanding that it see her world as she does.”

The scene marks a shift in Nehma’s confidence: “She has gained confidence because her supervisor believes in her. Nehma’s reasoning was valid, and she became visible. There is a ray of hope to change the AI / system.”

This act of quiet rebellion highlights a broader issue in AI ethics: when data lacks genuine representation, technology perpetuates the erasure and mischaracterization of marginalized identities.

Dr Joy Buolamwini, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, describes such distortions as “power shadows”, biases that are “cast when the biases or systemic exclusion of a society are reflected in the data.”

The AI-generated images of Nehma illustrate precisely this phenomenon: a system trained on unrepresentative data that mirrors existing patterns of marginalization rather than challenging them.

Meanwhile, a parallel storyline follows Nehma’s 12-year-old daughter, Dhaanu, who initially resists her mother’s decisions. As she slowly adapts to life in the village, she begins filming daily life, people, and landscapes in a way that only an insider can. These clips become the very material that helps counter the inaccurate AI imagery, reinforcing the film’s message that genuine representation arises from within communities themselves.

Invisible made visible

What surprised Madhushankar most about learning about this industry was discovering “the significant role that women play in this process,” despite working in conditions “that are overlooked or underappreciated.” Another aspect that moved her was “how human and emotional this work is, despite being connected to such a technical field.”

She reflects on the complexity of these opportunities: “In a different reality, I would celebrate the opportunities these women are getting. They are now able to earn a livable income to support their families, unlike earlier jobs that barely provided enough to make ends meet. While the working conditions are far from ideal and life remains challenging, these new types of jobs offer a meaningful chance to improve their lives.”

Reclaiming the human

Humans in the Loop reframes the global conversation about AI. By centering Nehma’s story, Sahay reveals that technological progress is not only engineered in labs but also built through the painstaking labour of women whose knowledge is intimate, embodied and often invisible.

The film insists that AI cannot be ethical, accurate, or equitable unless the people shaping its foundational data (particularly marginalized workers) are acknowledged, respected, and included in the narrative of innovation.

Madhushankar’s own perspective on AI has undergone a profound shift as a result of this role. “Before this role, I honestly saw AI just as a technical tool. Something I can use whenever I want and throw away whenever I feel like,” she admits.

“But now I’m realizing that AI sort of wants to create a dependency on it so that it can grow… I want to make mistakes. I want an email with imperfections and incorrect grammar. I want to treat myself humanely. I want to share my feelings with human beings who are imperfect, not with a chatbot that gives me prompt answers.”

This personal transformation reflects the film’s larger message. In a world eager to celebrate the sophistication of artificial intelligence, Humans in the Loop brings us back to a fundamental truth: before a machine can recognize a leaf, a gesture, or a face, someone like Nehma must first teach it what those things really are. And in doing so, she brings not just data, but wisdom, culture, and humanity itself into the machine.

Shailaja Rao is the executive director of eShe and founder of South Asian Lens Collective (SAL Collective). Email: shailaja@esheworld.com

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Loved the movies, brilliantly made, and what beautiful location, the porcupine, the rocks…very well captured.

LikeLike

Amazing story. May the film go on to win many Awards.

LikeLike