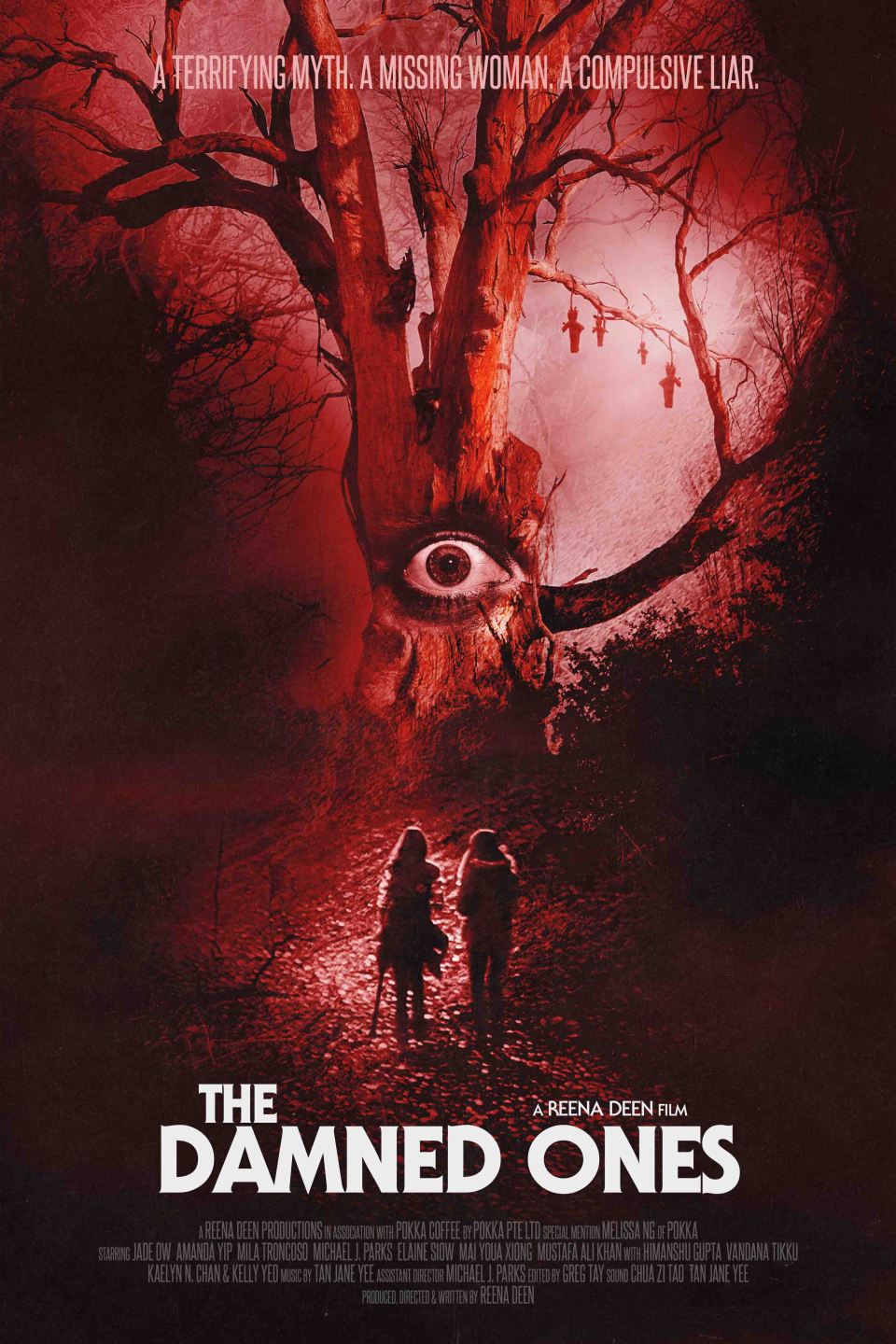

It was rejection as a writer that prompted Reena Deen to direct a film instead. The Singapore-based 42-year-old made her debut as a filmmaker this year with the short film The Damned Ones. The psychological mystery thriller, shot over three months in 2023 and released in early 2025, features a narcissistic character and includes supernatural and horror elements.

The film has already been extensively written about in local Singaporean news and in Canada’s largest horror-film magazine. A mini docu-drama that chronicles the filmmaking journey has also won two awards.

But what’s truly unique about this endeavour is that it has been made with a largely disabled cast and crew – a conscious choice by Indian-origin Deen (full name Zareena Nazimudeen), who is herself dyslexic and has complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) related to abuse as a child.

“I started out as a writer of books,” says Deen. “Issues like mental health, abuse and disabilities were often subjects I explored in my stories.” However, she faced “countless rejections” from agents and publishers “who felt my stories were too raw, too intense,” she says.

So, she decided to write a feature film script where she could explore these topics with freedom. “I had already taken a script-writing course and was an active member of a community filmmaking club called Kino Red Dot where I taught myself filmmaking,” she shares.

During a discussion, a Kino Red Dot member – an actor with a disability – mentioned that it was common for people with disabilities and their stories to be rejected. That was the moment Deen decided to create an opportunity for a film crew with disabilities.

“The funny thing is, initially, a lot of us were not open about our disabilities. Most of us had invisible disabilities that we had gotten used to hiding because of fear of stigma or loss of employment. It was only during the first film shoot that we began to slowly open up about our disabilities,” she shares.

After that, Deen began to actively look for supporting cast and crew with disabilities. Almost 80 percent of the final team of 34 had some sort of disability, she says.

Deen – who doubled up as the film director and cameraperson – spent SGD 7,500 from her own savings for the film production. Even so, the cast and crew were largely unpaid. “Many of us who have disabilities struggle to find even unpaid meaningful work in film that we can put down as experience in our resumes. So, this film served as an amazing opportunity,” she explains.

The film was considered a Kino Red Dot project as many of the team came from this community club. They too worked on an unpaid basis “for the love of the film craft and to promote the indie filmmaking spirit,” Deen says.

What does inclusivity on a film set look like? “Inclusion must always start behind the scenes. Scripts should be checked for bias and stereotypes,” avers Deen, sharing that the lead actors (one of whom is hard of hearing while the other is visually impaired) read the scripts and advised changes. Deen even rewrote the characters so that they shared similar disabilities as the actors.

Secondly, she had to make sure that sets were checked for safety. Next, there were discussions on accommodations needs. “For example, my assistant director is unable to read long passages hence he requested not to read the script. So, before each shoot, I would verbally explain the scene to him,” shares Deen.

Another challenge she faced was that some of the cast have a deaf accent. “Accent bias is a huge issue in film and media. Most audiences are not used to deaf accents, people who stammer or use a ventilator, or people with speech impediments.”

At the same time, Deen did not want a voice actor to dub for the cast “because that wouldn’t be inclusivity,” she says. “Their deaf accent was very much part of them, and I did not want to erase their disability and their true selves.”

To work around this issue, Deen wrote parts into the film showing the actors putting on hearing aids, so that audiences may understand why the actor has a deaf accent.

Another challenge the team faced was a shortage of shoot locations when organisations realised the crew had disabilities. “They refused to let us use their office buildings, citing risk management issues. I had been planning to use these buildings’ mini parks and gardens to fake a forest setting as Singapore has high heat and humidity, and shooting outdoors for a long period is hazardous to health. These locations would have allowed the crew to rest in the air-conditioned buildings in between takes and they also had accessible toilets,” she says.

Deen had to rewrite the script to minimise outdoor shoots, and then spent days searching for suitable outdoor spaces with shade and accessible toilets.

But, as she puts it, “inclusivity contributes to cinematic art because the world hears previously untold stories from perspectives that are authentic”. Such stories also resonate positively with viewers with disabilities – one in six persons has a disability, making it a sizeable number worldwide.

“Most of the time, stories about people with disabilities are written by abled people, and we end up playing stereotypical roles like the infantilised person, victim, villain or the inspirational hero whose disabilities are superpowers,” rues Deen. What’s more, she adds, the storylines often only revolve only around disabilities in such cases.

Deen wants audiences of her film to take home the message that “people with disabilities are people just like everyone else and therefore they can and should be acting in a variety of films and not just ones with a disability theme”.

She disagrees with the popular narrative created by “some well-meaning abled folks” that “disabilities are superpowers”. “Unfortunately, this idea erases the struggles we have because of our disabilities,” she states. “A disabled person has a disability and there’s nothing wrong with that. But we want the world to see us beyond our disability. We also have many other wonderful abilities.”

The problem, she says, is a world that is “hyper-fixated on perfection and chooses only to see what is wrong and not what is right”.

Citing her own struggle with dyslexia, Deen says her schoolteachers often punished and humiliated her by calling her names like “stupid, idiot, lazy, rubbish” and so on for bad handwriting or poor spelling.

Deen says she has, of late, finally begun to understand the true gift of dyslexia due to the work of award-winning British social entrepreneur Kate Griggs, the founder of the charity Made by Dyslexia, who has been writing extensively about the power of dyslexic thinking in the age of artificial intelligence.

“I realised that many of the things I did effortlessly, such as employing lateral thinking for complex problem solving, or coming up with creative solutions, were very much part of my dyslexia. Without these skills, I honestly would not have been able to overcome so many obstacles and make this feature film,” she says.

Deen hopes to see others make movies like hers where people with disabilities are able to contribute to scripts that don’t revolve around disability. “Media is a powerful tool. It is my belief that if we can increase positive and authentic representation of people with disabilities in the media, we will slowly but surely eradicate the prejudice and stigma against disability in society,” she concludes.

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “This Indian-origin director is reframing the narrative around disability representation in film”