By Apoorva Gairola

We are on the verge of entering the last quarter of 2024. It is a fateful year for democracy, with more than half of the world’s population voting in elections before its close, making individual and collective choices in the ‘free’ world and contributing to the local and global future of humankind. A year that tests democracy as much as it celebrates it.

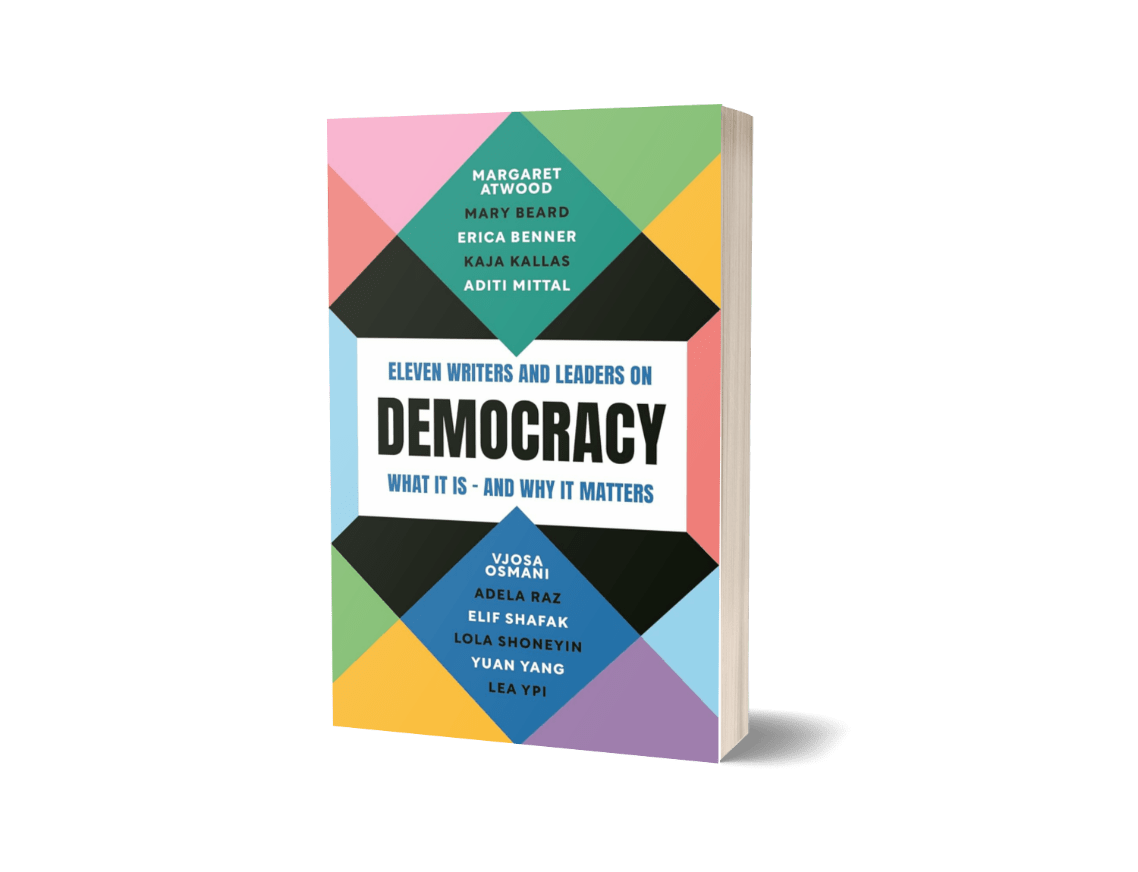

Identifying, addressing, and acknowledging its significance and urgency, the Financial Times and Profile Books have published Democracy: Eleven Writers and Leaders on What It Is – and Why It Matters (Hachette India, INR 299). The book is a collection of eleven pieces of writing by women from diverse personal, professional, and geographical backgrounds. Each has contributed their personal as well as professional perspectives on what the widely used but not always understood term ‘democracy’ means to them.

Award-winning British-Turkish novelist and storyteller Elif Shafak contributes the first essay, ‘Terra Incognita’, a Latin term which translates to ‘unknown territory’. And unknown it is, for the world we knew is gone, and change in all its multiplexities is too fast-paced for the best of us to fathom, leaving us in what she calls the “age of angst” where anxieties and fatigue overshadow life and sanity.

She refers to democracy as “a delicate ecosystem – of checks and balances, rights and needs, power and accountability,” and emphasises the need to register that we are travelling through this unknown territory together, that our identity is in “multiple belongings”, that apathy in the face of uncertainty is no longer an option, and that we will survive this journey together if and only if we regain the ability to see each other as human.

Professor emerita of classics at the University of Cambridge and the classics editor of the Times Literary Supplement, Mary Beard reflects on the origins of modern democracy in ‘Demokratia’. She highlights some positives like changing one’s mind or having a second referendum on a contentious political topic as being non-prohibited and even welcomed, while also shedding light on the fact that chattel slavery coexisted with “freedom for a few” in Athens, our democratic ancestor.

She argues that people are still enslaved today, even if turning a blind eye makes it acceptable. Lastly, she urges us all to recognise that what we often look up to as an ancestral ideal is a political idea that is outdated and just not applicable in our present-day circumstances, “It is not so much that we’ve been led astray by a mythical democratic ancestor – it’s that our own heads are firmly in the sand.”

Lola Shoneyin, a Nigerian author, poet, publisher, bookseller and festival organiser, talks about democracy as “a fragile state” in a poem. “Memory is tied to a stake, history silenced by firing squad. The sword decapitates the pen, spilling blood on every page. Words are no longer enough to keep the wise alive,” she writes. She goes on to stress the importance of protecting democracy and revising it by “hammering out its imperfections, pounding it, moulding it, baking it in the kilns of our histories.”

Lea Ypi, professor in political theory at the London School of Economics and an honorary professor in philosophy at the Australian National University, reflects on democracy as being synonymous with freedom, starting with the freedom of movement in global emigration and immigration, the lack of which is a condition of unfreedom.

Then comes freedom of thought, which under current circumstances of algorithmic manipulation is effectively done away with. While liberalism has the promise of freedom (from fear) at its core, when married to capitalist society, it only ends up producing and reproducing anomalous pathologies of its own. For this very reason, liberalism fails and is inadequate in delivering. Liberalism means to restrict any collective organisation that hinders the freedom of the individual, but the liberation of the individual also encourages selfishness and indifference to the fate of others.

She proposes that educating and enlightening people, highlighting moral double standards, the difference between how we think of freedom and how it actually exists, and adding and upgrading material incentives for participation may be a few ways to introduce change. “We live in a world of injustice replicated by anonymous social structures,” she says, “And a world in which not everyone is free is a world that cannot be truly free for anyone.”

The present and first-ever woman prime minister of Estonia since 2021, Kaja Kallas advises that democracy should embrace its own power instead of fearing it, and includes some lessons that we must learn from the story of democracy in Europe.

The lessons include taking bold decisions as opposed to wishful thinking; we must be vigilant, for opponents will use existing divisions against us; and that we must do whatever it takes to protect our democracies while there is still time.

Erica Benner, a political philosopher, historian of ideas, and academician, writes about democracy in terms of human progress, and while the term itself is loaded with the promise of progress, its existence often reveals the lack of it. She expresses concern over the growing mistrust in democracy and the “spread of global pessimism about the superior merits of democracy.”

Democratic freedom is about power sharing, about limiting certain personal freedoms that would ensure there are opportunities and options for everyone else, she says. “It’s time to abandon the idea that people from powerful countries are uniquely qualified to design and build democracies for others,” she advises. A narrowed-down, simplistic view of the merits of democracy over others is a place to begin identifying what needs to be done to protect it.

President of the Republic of Kosovo, Dr Vjosa Osmani-Sadriu writes about her experiences growing up under the Milošević regime, where their basic human rights were violated in unmentionable ways. She talks about democracy as a way of life, which is “the antidote to tyranny, the bulwark against oppression and the guarantor of our most cherished freedoms.” She emphasises on the importance of action in realising and maintaining the democratic rule and the relevance of women’s participation.

Democracy is the temperate zone, says renowned author Margaret Atwood, whose latest novel, The Testaments, is a co-winner of the 2019 Booker Prize. The temperate zone, which falls between the political left and right, extreme left and right, and stands between dictatorship and chaos, “respects the concept that those ruled ought to have a say in their rulers.” Rulers must be accountable to the rule of law; a dictator should not control the judiciary, and freedoms of religion, debate, and peaceful assembly should be valued and protected.

She talks about dictators believing in their privileged right to rule as the chosen ones and having no concern, in fact, an ‘ingrained contempt’ for the common man. The way to save our democracies from falling into the hands of dictatorship, according to Atwood, is to educate people and strengthen existing democratic institutions. “Call the bluff,” she ends.

Afghanistan’s last ambassador to the United States, Adela Raz, was also the first woman to hold the position of permanent representative and ambassador of Afghanistan to the United Nations. In her essay, she says democracy as an ideal never failed in Afghanistan; in fact, under the right circumstances, Afghan people would still gravitate towards it.

What went wrong was the way it was introduced and established as a centralised power structure, designed by Western policymakers who did not consider the divisions and diversity in the Afghan population and the interests and grievances of Afghan society. Despite being well-intentioned, this was a fundamentally flawed imposition where the people being ruled lost faith because “the consolidation of power enabled self-serving actions.”

People began to believe that decisions and policies that dictate the quality of their lives were being taken by foreign authorities and figures as opposed to the Afghan people’s elected representatives. This distrust, which she calls a “crisis of confidence”, is not limited to Afghanistan but spread globally, especially among the younger generation.

“Any system of governance, whether democratic or authoritarian, must align with the society it governs,” she adds. When the government does not reflect people’s values and an outside imposition is present that undermines the very basics of a democratic framework – freedom and choice – it is not possible for any governance structure to last in the long term.

The monotony of the written word is broken with a visual and short script by Indian comedian, writer, and actor Aditi Mittal. Through a heartwarming conversation between an elderly retired father and his daughter in a middle-class Indian household in Mumbai, Mittal highlights how democracy is perceived by Indians in a relatively young democratic country.

While the father refers to it as an illusion of choice, the daughter relates to it as simply the right to wear whatever she wants, calling it her freedom of expression. “The world can make a woman, Papa, but only in a democracy can a woman make her own world,” says the daughter.

Yuan Yang, a Labour Party politician in UK, shares her experiences while living in Beijing and discusses the importance of community participation for democracy to exist and thrive. She says that democratic rule is only possible through collectives: “The organised expression of collective interests is what gives shape and meaning to democracy, and requires trust, continuity, structure – and the willingness of people to join things.”

Even those without noteworthy interest in world politics will find the book to be intriguing, captivating and informative. The diversity in the content and writing styles only adds to the appeal. It’s a short read but one that’s meant to be deeply engaged with.

As the world moves through growing inequality, diminishing freedom and flourishing injustice, this may be another effort in fighting for and protecting “the most important political idea the world has ever known”.

Apoorva Gairola is a psychology professional and former journalist who is passionate about mental health, women’s and gender issues.

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks. More later soon! Shakil Ahmed (Shokee)Lahore Pakistan

LikeLike