Roxana Shirazi is an Iranian-origin UK-based author, journalist, and actor whose work explores identity, exile, and sexuality through a feminist lens.

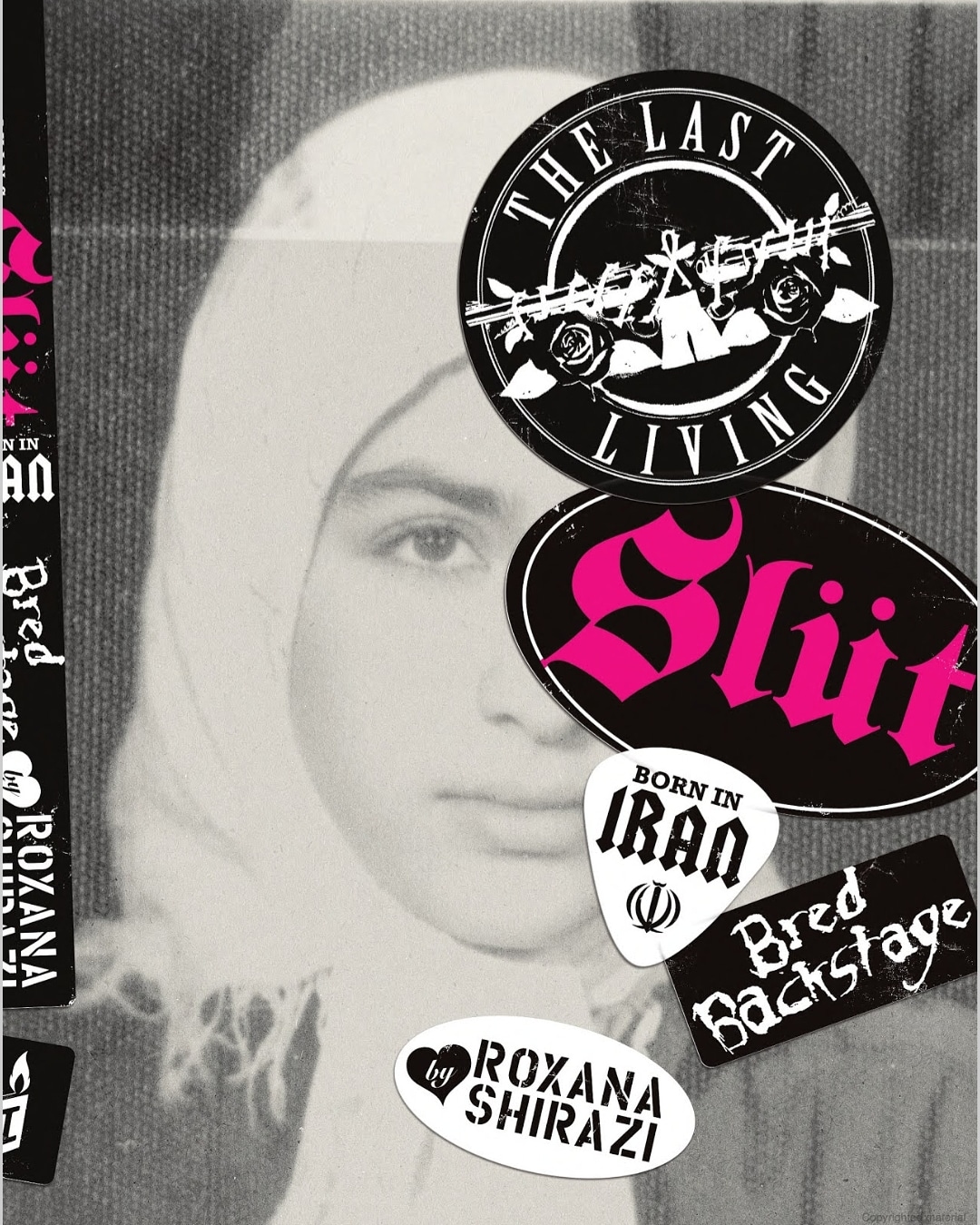

Her 2010 memoir The Last Living Slut: Born in Iran, Bred Backstage (HarperCollins) drew attention for its candid portrayal of life between revolutionary Tehran and the world of rock ’n’ roll in the West, replete with graphic descriptions of sex and female sexuality. But it also cost her economic opportunities, besides making her persona non grata in her birth country.

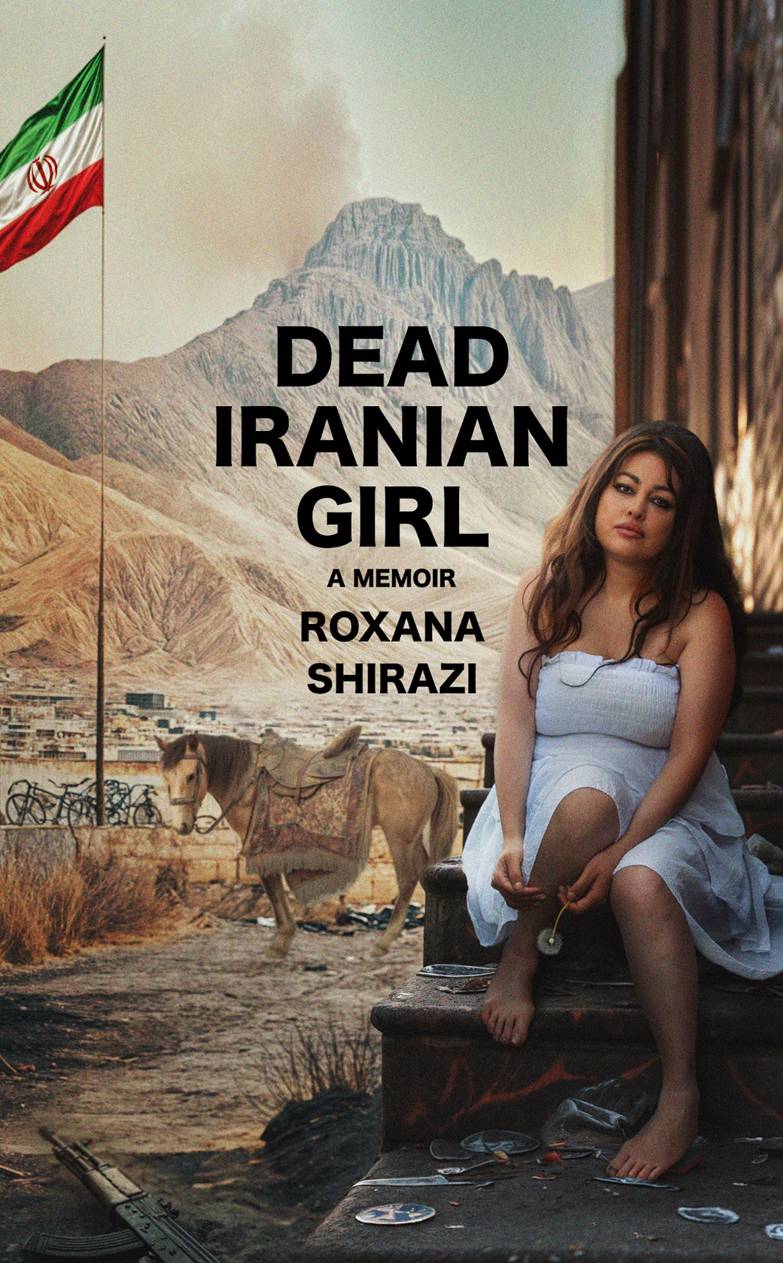

A self-described gonzo journalist, Shirazi has written from within the situations she covers – from encounters with the Ku Klux Klan to being smuggled into Iran. Her new memoir, Dead Iranian Girl (2025), was named runner-up for the Footnote Counterpoints Prize for nonfiction by a writer from a migrant or refugee background.

This excerpt from Dead Iranian Girl is being published with permission from Rare Bird, Los Angeles, California.

By Roxana Shirazi

Tehran, 1973. My mother was milk-soaked when they came for her. The damp blotches spread like water lilies across her blouse which annoyed her more than being taken to prison for freedom of speech.

I was six months old. Soft, useless, squinting into the bright slap of the day, unaware I was being taken to prison. The Shah’s secret police, SAVAK, had raided my grandmother’s home bashing down the front door and ripping apart furniture in search of anti-Shah literature one afternoon as my mother nursed me.

They arrested her for anti-Shah political activity and, before my grandmother’s terrified eyes, the five of them bundled her into a car. But not before she had insisted on bringing me and my nappies with her.

Once inside the interrogation room, she had been blindfolded and braced for the torture that was the fate of all political activists while I was handed over to the guards. She was questioned about her friends’ and family’s political activities but she had refused to talk, so after 24 hours they had snapped, telling her to get out. She had grabbed me and run.

Being a socialist revolutionary in resistance to the Shah’s totalitarian regime, a dictatorship with little social and political freedom, was more important to her than anything else in the world, and she continued her activism even when she took me to the school where she taught literature. She was 24 years old, with ironed hair (with an actual iron) that for years had reached past her buttocks but was now hacked to a shorter, more modern vibe.

She had had an army of suitors since her late teens, coming far and wide from villages and towns to ask for this graceful well-bred beauty’s hand in marriage. It was her Tabrizi porcelain skin and come-hither cat eyes and mermaid hair and the fact that she was from a noble class, her family being educated, cultured landowners.

But she aggressively pursued the anarchic and the antagonistic to societal norms – the nice safe doctor husbands she was supposed to settle with, like all her cousins and friends – and hooked up with a tall silent poet, Nasser, whom she had met at university, both studying literature and psychology.

With her short skirts and poker-straight hair (all her friends still wore their hair in the outdated 1960s puffed-up bouffants and backcombed beehives) and he with his bell-bottoms and platform heels and tinted eyewear, they made for a handsome couple. Except his allegiance was to opium and poetry and not to being a political activist and revolutionary like her.

Before I was born, he’d completed the compulsory military training, with them living in the barracks, and she had lain awake at nights, anxious that this man – distracted, sluggish, pacified by poppies –could be anyone’s father. The opium made him so mellow and laidback that it transitioned into being apathetic and uninterested in parenthood.

He had been absent on the day I was born in the Soviet Military hospital in Tehran in September 1973. Pain relief was considered bourgeois indulgence and the nurses slapped and kicked her when she didn’t push hard enough, as if cruelty would expedite dilation.

In keeping with the stoic philosophy to childbirth, she had been deprived of water for hours to experience extreme and prolonged thirst and left on the table – perhaps to inspire maternal grit. At one point she had even thought about running away from the hospital.

In line with the institution’s dogmatic minimalism, mothers and newborns were kept apart. For seven days, nurses wheeled me in like a dairy delivery, granted her a few minutes of breastfeeding, then wheeled me out again convinced that that their strict, almost militaristic routine was in the patient’s best interest.

She named me Negar, meaning ‘beloved’ and ‘sweetheart’, and we lived with my maternal grandmother Ashraf, whom everyone called Anneh – meaning ‘mother’ in Azari dialect, because she was a mother to everybody who met her. A bright sunny energy, almost celestial in aura, people far and wide flocked to her home, which was the hub of food, love, gatherings and afternoon siestas for neighbours, relatives and even my uncle’s political activist friends hiding from the SAVAK.

My father, who was never around and was mainly hanging out with his own mother and siblings in a house not far from us, had taken to stealing some of my mother’s earnings, sometimes hidden under the rug, for his addiction, and so my mother did the unspeakable.

A divorced woman in 1970s Iran had massive social stigma, let alone one with a young child, but my mother went ahead and got a divorce. This probably added more cachet to her trendy identity as a revolutionary-poet-feminist-teacher with a young daughter.

She left me with Anneh when she went to work, teaching all day to provide for me and my grandmother, just like she had done before I was born for her parents – all her wages every month had been handed to her father who was crippled after a stroke.

Life was meant to be hard, otherwise you weren’t a real socialist.

Lead image: At a rally in London on 29 April 2023, calling for UK to declare the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps a terrorist organisation (Photo: X / Roxana Shirazi)

All photos credit: Roxana Shirazi

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “The rebel’s daughter: Roxana Shirazi on activism and motherhood in Shah’s Iran”