By Shailaja Rao

This is a crucial moment to amplify women’s voices and experiences, especially those of Afghan women, when governments actively work to silence them. And California-based Ankita M. Kumar understands the urgency of elevating women’s voices intimately.

“Women’s voices are continuously and consistently silenced by governments across the world,” says the award-winning Indian-origin journalist and documentary filmmaker whose accolades include an SF Press Club award and the Professional Excellence Award from the Association of Foreign Press Correspondents.

“It’s important that we bring to light stories about women, told by women,” she states.

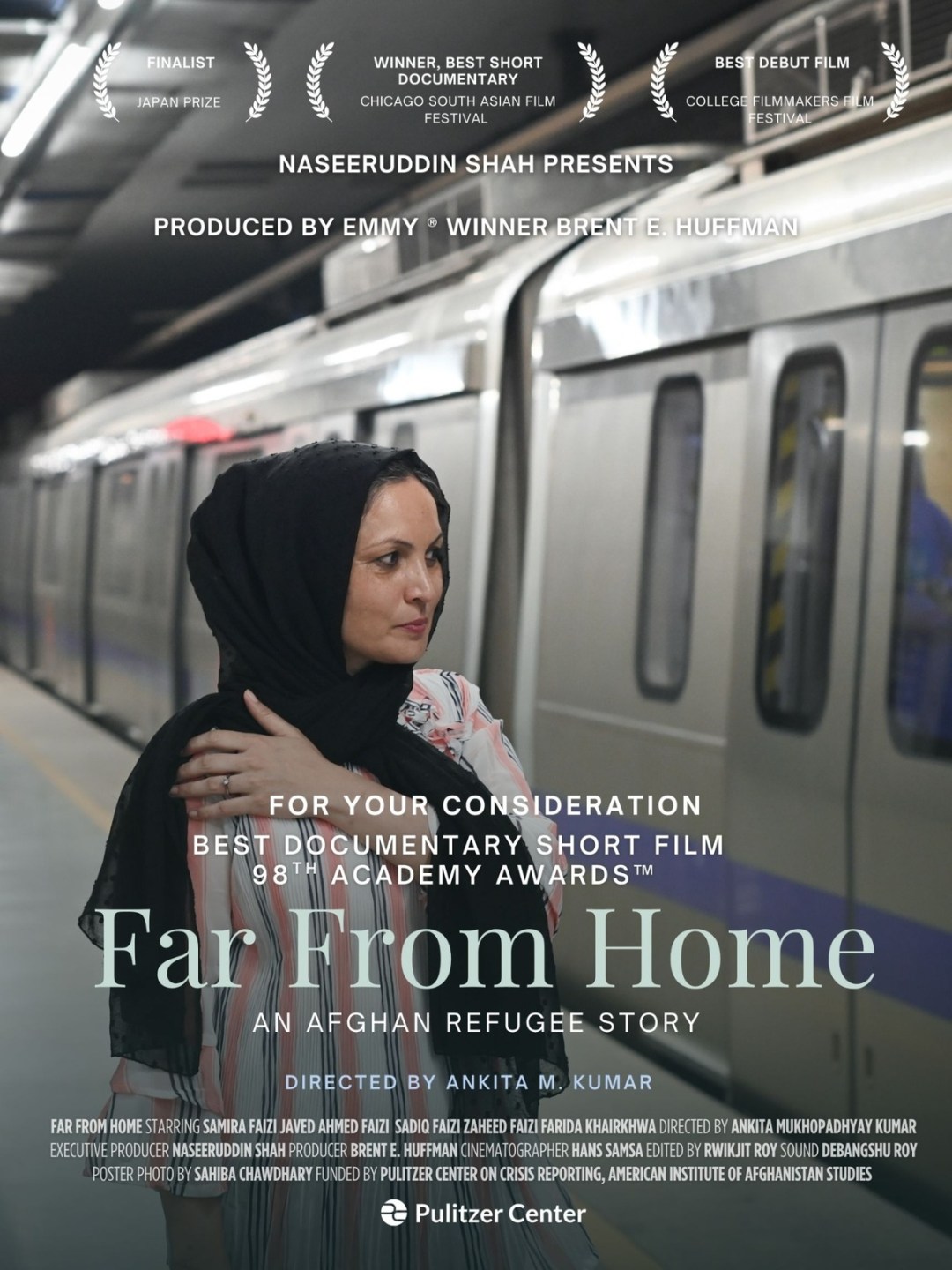

Her 2024 film Far From Home embodies this mission. The film won the Short Documentary category at the 2024 Chicago South Asian Film Festival, qualified for the 98th Academy Awards, and was a finalist for the Japan Prize. Most notably, it has attracted acclaimed actor Naseeruddin Shah as executive producer, a significant endorsement of its power and reach.

“I’ve always believed the most important function of cinema is to act as a record of its times. For this reason, I consider documentaries to be of more value for posterity than features,” Shah said in his endorsement.

Far From Home follows Samira Faizi, an Afghan refugee who fled to India in 2021 after the Taliban’s takeover. Now Samira navigates India’s hostile immigration laws and rising anti-Muslim sentiment. Produced by Emmy winner Brent E. Huffman, the film is more important than ever today. The Indian government’s new immigration act, which came into effect on September 1 this year, provides relief to refugees who came to India before December 31, 2024, but specifically excludes Muslims.

Existing at the intersectionality of religious and gender-based discrimination, women in South Asia face exclusion and institutional barriers on other fronts too. The issue was underscored during Afghanistan’s Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi’s recent week-long visit to India.

When women journalists were excluded from his first press conference, the deliberate erasure sparked immediate outcry. Within three days, after sustained public pressure, women journalists secured access to a second conference where they finally questioned Muttaqi about the plight of Afghan women and girls.

Ankita Kumar, who graduated with a Master’s degree from Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism in 2022 and is an alumnus of the London School of Economics and Political Science and Lady Shri Ram College in Delhi, visited Seattle recently. We discussed the making of the film and her vision for amplifying silenced narratives.

The film has had quite a journey so far. Can you talk about it from when you started three years ago, and how you managed to fund a project with such a specific, marginalized focus?

I have always been passionate about reporting on refugees and marginalized communities – in fact, my thesis project in my documentary class at Northwestern was on Afghan refugees in Chicago. I wanted to bring to the fore stories of refugees in parts of the world where they are typically overlooked.

Before I graduated in 2022, I was selected for a postgraduate reporting grant by the Pulitzer Center. It was a generous amount that allowed me to make my foray into documentary filmmaking.

The universe also aligned in a beautiful way when I received additional funds from the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies to finish the film.

If you have conviction in your story and know what emotions you want to evoke, you can make a film on any topic. But you must believe in your story and, above all, believe in yourself.

How did you find Samira? What was the process of earning her trust? How did you decide what to show and what to hold back?

The original subject of my film backed out at the last minute, citing fear of persecution from the Taliban. After she left, I was literally stranded on the roads of Delhi with the cinematographer, camera assistant and equipment. We were clueless on how to proceed.

But I think I was destined to make this film. I met Farida (who also features in the film), who introduced me to Samira. It was such a pleasure to work with Samira – she opened up quite easily and trusted us with her story. I think when the subject realizes that your intentions are pure, they are convinced to open up.

I was also lucky to have the best cinematographer, who has an innate ability to be behind the camera, yet disappear. After a point, Samira just forgot about the camera and let us follow her around everywhere.

We actually have a lot of footage that we couldn’t put into the final film, including of other Afghan women such as Waheeda. We really wanted to include footage of Samira telling us how she learned Hindi from watching Bollywood films!

I think as filmmakers we get emotional and try to get as much as we can in a short amount of time, but we knew we had to hold back and tell the most important story of the lot – that of Samira’s fight for survival. That helped us stay focused.

What did making this film cost you emotionally?

The making of a film on such a serious topic takes an invisible toll on you. I started seeing the effects of this after the shoot ended. Suddenly, there was a silence I had to navigate. I was obviously very frustrated about their situation and there were times I wished I was an activist, rather than a filmmaker.

But I eventually came to the realization that filmmaking is a tool to bring the truth to people. The fact that I had made this film – and no one had ever made a film on this topic – gave me enough emotional ammunition to cross the finish line and take Far from Home to multiple film festivals as well.

Did your perspective on Afghan displacement shift through the process?

I did my undergrad in Delhi and I was well aware of the impact the Afghan community had had on certain neighborhoods in Delhi. But I didn’t have an idea of the extent of the displacement.

When I visited their homes and spent significant time with them, I realized that their displacement mirrored that of any refugee family (including my family, which was displaced during the 1947 Partition of India). When you have to leave your home and become a refugee, you see education as a pathway for economic opportunities.

These Afghans were displaced physically, but it didn’t deter them from striving toward their dreams. They want to overcome their circumstances and become economically independent. But unfortunately, they are in a country where they will always be in a limbo situation.

Apart from the film, I also wrote an article for The Wire, contrasting my grandmother’s experience of Partition with Samira’s current displacement.

What do you hope the audience takes away? How do you see this film contributing to policy or cultural change around refugee narratives?

I hope the audience understands that no one becomes a refugee by choice. That refugees are humans as well, with aspirations and dreams. I see this film making it to schools and universities, where students study and understand the psyche of displacement and its impact on refugees.

I would like this film to lead to political change so that countries that do not have a refugee law put a framework or pathway in place for people to integrate, or generate at least some form of social mobilization.

I am grateful for the assistance of Bollywood actor Naseeruddin Shah on this journey. He recently came on board as its executive producer – in fact, this is the first time he is an executive producer of a film!

What are you working on now?

I am now working on a feature documentary on the lives of Aishwarya and Saundarya – the great-granddaughters of MS Subbulakshmi and granddaughters of Radha Vishwanathan. This is my first feature and it’s on a topic extremely close to my heart – Carnatic music – and I can’t wait to bring the film (and music) to the world.

Shailaja Rao is the executive director of eShe. Email: shailaja@esheworld.com

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “This Indian-origin filmmaker is amplifying Afghan refugee voices”