In her new book The Art of Decluttering (Penguin Random House India, ₹399), Bhawana Pingali writes about almost-forgotten Indian lifestyle rituals and practices, which, she says, can be tweaked and integrated into modern life to enhance physical, mental and emotional wellbeing.

Through stories of ancestral memories, objects and emotions, Pingali nudges readers to reconnect with their own heritage, and find their personal blueprint of practices.

This excerpt from the book is published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

By Bhawana Pingali

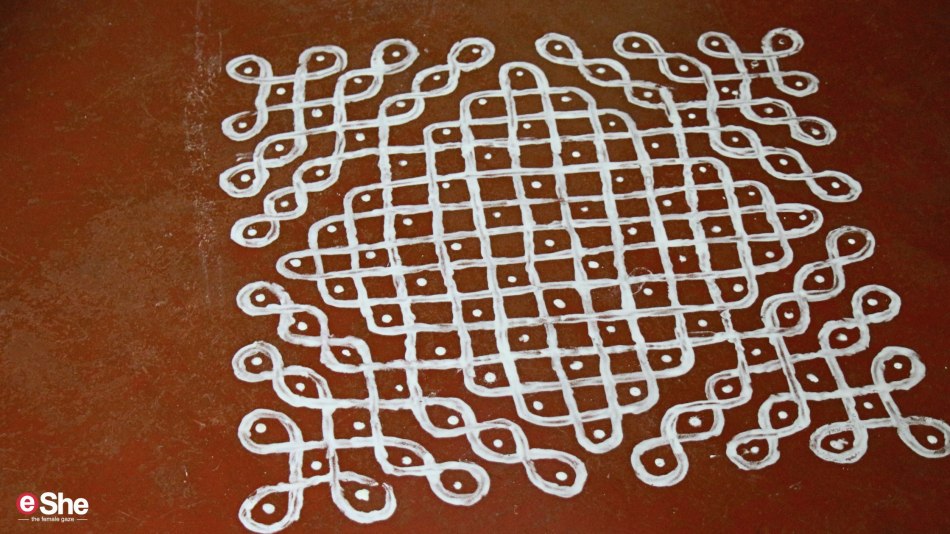

The word muggu comes from Telugu and means patterns hand-drawn on the floor using rice flour. An over-2000-year-old oral tradition, it is known as kōlam (beauty) in Tamil Nadu, alpana in West Bengal, sathiya in Gujarat, aripana in Bihar, muruja, chita or jhoti in Odisha, chowkpurana in Chattisgarh, mandana in Rajasthan and rangoli in some states in north India (although this form is colourful).

Research finds the earliest references to the art form in Sangam literature (300 BCE to 300 CE), where it is mentioned by Andal, the female Vaishnavite saint who was one of the 12 Alvars (Tamil poet-saints in south India). From that time, kolams and muggus, intricate drawings made of wet and dry rice flour, were thought to represent wellness in a home.

Across Andhra, Telangana, Odisha and West Bengal (and surely other states), I have seen floor art – prayers, hope, love and longing turned into white designs – made with fingers, palms and hands, even hay, straw or twig brooms.

Including its wall and palm leaf folk art variations like Warli and Pattachitra, they are made individually or collectively, while standing or sitting. These curvilinear variants, using rice paste instead of powder, can go outwards, inwards, upwards, sideways and downwards – crawling up walls, doorways, windows and ceilings. Some floor art also has special places like cooking stoves to show respect to the fire god.

Alfred Gell, in his book Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory, describes kolam as sinuous and symmetrical figures that are “difficult to read”, in the sense that it is very difficult to see how the design has been constructed. He also says that like in mazes, kolams play topological games. There is “cognitive teasing” that goes on here – the loops are difficult and “frustrating” to “read”. The “cognitive stickiness” of the loops blocks reconstruction of the patterns by an outsider.

No wonder then, he concludes, that even demons are scared to cross these “sophisticated topological snares”. The designs connected by dots and lines that I saw in my childhood were similarly repetitive and confusing. And belief based.

Bengaluru-based art and design pedagogue Dr Geetanjali Sachdev has contrasted wall-art patterns with floor art in her studies. Her PhD thesis, titled Petals to Light . . . Pedagogic Possibilities with Floor Art, explores rangoli and kolam floor-art practices to understand their pedagogical potential for the study of plants.

The research also involved an analysis of a personal archive of rangoli and kolam images, and a series of artistic collaborations. Dr Sachdev suggests that wall surfaces mostly depict secular and other themes, and floor patterns are created for festivals and celebrations.

They are expressions of reverence related to natural phenomena, such as eclipses, lunar and solar cycles, stars, solstices; landscape elements such as rivers and hills; plants and animals; supernatural aspects of life such as the spirits of our ancestors; and Hindu gods or mythological events.

Dr Sachdev told me that the muggu from my past (Andhra) is interpreted as a form of solar worship (done early in the morning) and a prayer to the feminine essence of the sun god (performed by women).

Bhubaneswar-based soul curator, transformational coach and healer Dr Vedula Ramalakshmi told me, “Muggu lived through periods as an ancient art form for home decoration when the concept of framing pictures or other current forms of wall art didn’t exist. That is why they were done on floors, walls, doorways and other places inside and outside the house to beautify, symbolise and cleanse spots and spaces.”

She explained muggu and kolam’s symbolism to me. “From what I have understood based on my experience and studies, symbols like gummadikaya (pumpkin), pachani gummadi puvvu (yellow pumpkin flower), uyyala (swing), dhanushu, villu banamu (bow and arrow), nalagu dwaralu inka pantendu dwaralu (four and 12 doorways) and others made before and after Sankranthi festival depicted harvest, fertility and prosperity. They allowed all positivity and pleasure to come in. A pumpkin creeper and its flowers grow without hindrance. It represents love and how bonds or relationships in life can also flow and grow.”

Other than design symbolism, “a lot of people still believe that muggu or kolam inside homes have sacred and energetic effects on people who live in it,” Hyderabad-based homemaker and mother Varalakshmi Vedula (a distant aunt who does muggu regularly) tells me. Dr Ramalakshmi agrees but says you may not find scientific evidence to prove this.

Nandini Srinivasan in a podcast interview with Dr Vijaya Nagarajan, lyrically connects this ritual art to Goddess Lakshmi and calls it “sacred”, “yogic” and “therapeutic”. Alfred Gell calls kolam, muggu and other eastern states’ works of art “threshold designs” with spiritual angles: A) associated with the protective, fertile and auspicious cobra (nag); B) apotropaic (believed to protect against evil or bad luck) function, repelling or ensnaring demons.

Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at Ithaca College, Marcia Ascher notes how women of Tamil Nadu (also Andhra, Telangana and some in Karnataka and Kerala) sweep their thresholds every morning, sprinkle them with a solution of cow dung and water and cover the area with elaborate symmetrical figures using rice powder.

Traditionally, cow dung, Professor Ascher says, purifies the ground (or thresholds). She says thresholds are believed to be the boundary between the inner and outer world. They guard the house from negativity and welcome positivity of visitors. Hence, keeping these muggu or kolam “canvases” clean and welcoming was a must-do.

Aurogeeta Das in her paper writes how in Andhra, muggus are made at devalayams and devasthanams (sacred places, temple towns and spots), fronts of gopurams (temple structures), commercial establishments, kalyana mandapams (wedding halls), homes, side entrances, domestic shrines, kitchen counters, around buttermilk churners, on hand grinders and in courtyards (especially in front of the holy basil plant, or tulsi). The doorways at the thresholds were also fiercely guarded and feared.

In short, ritual creativity bubbles at the root of these transient forms that thrive on thresholds.

Lead image: Ajaykumar Menon

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “The faith and psychology behind Indian muggu (rangoli) floor art practices”