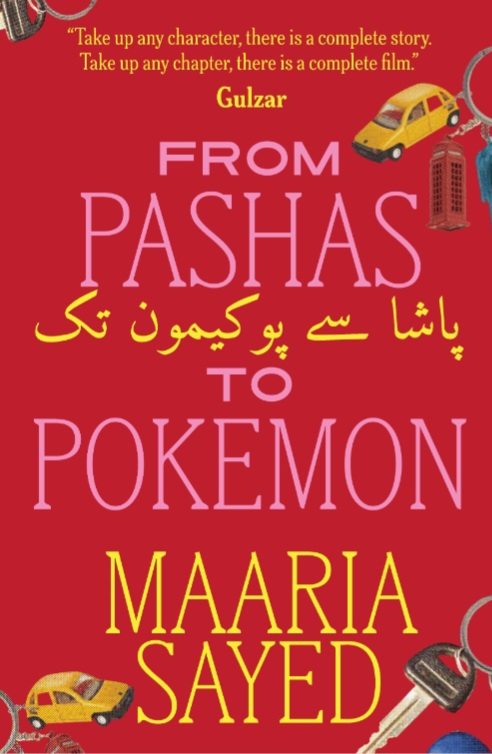

Desire and derision coexist simultaneously at many points in Maaria Sayed’s new novel From Pashas to Pokemon (Vishwakarma Publications, INR 275). Such as when a 25-year-old London-returned Aisha thinks of Hollywood flicks and world cuisine while her grandfather talks of his hatred of everything British and American. When the Muslim protagonist is scolded for wearing a Ganesha pendant by a conservative aunt, who nevertheless enjoys hearing that her own son looks like an avatar of Krishna.

When a middle-class father argues relentlessly why staying home in India is better than moving to the US, but quietly funds his son’s wish to head to Silicon Valley. When, instead of taking forward a relationship with a boy she is “painfully in love with”, Aisha cheats on him instead.

The book’s narrative snags the reader in a subliminal way, its characters evoking admiration and disappointment simultaneously at times. Coming from the pen of a filmmaker, it is no wonder that the episodes in the novel are almost filmi in flavour.

An alumna of London Film School with several acclaimed shorts and experimental films to her credit, Sayed’s work as a director has focused on the sexual and spiritual liberation of South Asian women and evolving Muslim identities. Her debut novel is no exception.

In this interview, the 34-year-old Mumbai-based writer and filmmaker talks about writing the novel in the format of a memoir; her fascination for the crowded, old Mohammed Ali Road; and why she felt the need to bring up ‘Islamic terrorism’ as the ‘elephant in the room’.

Why did you decide to write this novel? What inspired you?

The complete truth is that I was writing free-flowing thoughts for a few weeks. It was probably a reaction to the fact that I had just moved to a tiny mountain village in Italy and had got married a year earlier. And suddenly you have that moment in life when you process things.

I think I processed my growing years then. I missed the 1990s, my childhood and teenage years. It was a way for me to explore that era and create situations that I never actually managed to explore. A few weeks of writing later, I realised that there was probably a novel in there so I started structuring it out.

What are your thoughts on South Asian women achieving a more holistic understanding of the self through sexuality?

It is hard because, as a society, we just don’t talk about sex as much as we should. There are religious, patriarchal and political factors at play. I believe women need to talk about sex without it being sexualised. I believe embracing sexuality is embracing yourself and somehow this vulnerability makes you a better human being.

I try to get my women protagonists to embrace a part of themselves through a kind of self-discovery. And for South Asian women in particular, I think we all need to be comfortable discussing sex with each other and not label other women who do. This is the first step.

We need to see ourselves through our own eyes, not through the eyes of the men or systems around us. That’s the beginning of liberation.

You’ve touched upon ‘Islamic terrorism’ and put it in the context of a middle-class Muslim family in Mumbai. Why did you decide to write on this subject?

I believe in calling out the elephant in the room but in a discreet manner. I don’t like anyone’s bad traits or wrongful acts to be the primary markers of their identity. I like to see the humanity and different shades in everyone.

Thus, I felt it was important to talk about the effect of labels on people and families. Labelling any colour, caste, religion or community has deep psychological effects on the person and society at large and this penetrates all economic classes. In a strange way, you are taught to fear your genetics and roots because you start seeing yourself through the eyes of others.

This is internalisation of criminality in a layered way because you start labelling yourself too. So, yes, I don’t believe the words ‘Islam’ and ‘terrorism’ should ever be uttered in the same sentence. I hope that can be normalised someday by both Muslims and non-Muslims.

Though cinema and literature are both creative activities, what would you say is the primary difference in the creation and the production of any film versus a book? Which one is more satisfying to you?

Writing for me is entirely an internal process. It is hard for me to share that with anyone. So, yes, literature is a lonely and reflective way to take a deep dive into yourself, your surrounding and the world at large, I suppose.

The research process for writing both might be similar but I consider film more practical in a way. Everything needs to come to life in a visual way so you need to be less dreamy or at least find a way to turn that dream into a reality. With literature, it can be a dream all the way.

However, I do believe that being a person who is equally invested in both, my films can be a little dreamy and my literary work is a little visual in a practical way too. Depending on the phase I’m going through in my life, both can work like oxygen for me!

The characters in the book are so well-etched, they seem almost familiar, full of contradictions and grey shades. What was the most challenging (or the most fun) part of bringing these characters to life?

Thanks for that. I don’t think I’ve ever considered anyone a saint or a sinner in all my life. As a person I tend to see the grey in people, and I do acknowledge that in myself too. I believe we are all vulnerable, filled with insecurities and quirks.

As a writer, I am deeply in love with all the characters I create and especially their shortcomings. I think that’s what makes them human. At the end, I ask myself: does this character feel seen and loved? What does he or she want but not express? I think that’s the point I start off with, not just with characters but people I meet in my life too.

The book is written more as a memoir than a novel with a beginning and end. What prompted you to use this format for your debut novel?

I wanted this to seem intimate. I didn’t want the barriers that emerge when one speaks as an outsider. I wanted you to feel Aisha’s breath, her stammers and her insecurities and, despite all of them, to love her. After all, she is giving you a glimpse into her innermost thoughts and feelings, even when she is wrong and judgemental.

Writing in first person came quite naturally to me. It was important to make the reader feel the growth and the vulnerabilities of a girl who can also change her mind! She isn’t perfect but she hasn’t formed her judgements as an adult either.

What is it about Mumbai’s Mohammed Ali Road that fascinated you so much? The locality has a character of its own in the book.

Personally, I’ve spent a lot of time in these areas of Mumbai. I’ve had extended family who lived there and I made my initial short films there too, so it was months and months of research and days spent just absorbing the atmosphere.

I found an inherent street-smartness coupled with innocence and love in the people I interacted with there, and I wanted to keep that trait alive in my characters and eternalise them in my own humble way.

You’ve been a delegate and jury for the UN-backed Asia Peace Film Festival in Pakistan. Peace initiatives between India and Pakistan are at a roadblock of sorts, but when Indians and Pakistanis meet outside of their countries, there is usually camaraderie and a sense of cheer. What do you think of this contradiction?

There is no denying that we share culture, language, history, food, family history and God-knows-what-all. Naturally, we have also grown in different directions over the past few decades but there is still a sense of familiarity.

For a common person, interactions are smooth and essentially great, but I’m going to state the obvious: politics! If our political leaders would change their policies and allow us to be friends, I think it is the easiest friendship we’d cultivate. Loving our neighbours is another way of loving ourselves!

Discover more from eShe

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

0 comments on “A Muslim in Mumbai, an Indian in London: Maaria Sayed’s debut dwells on identity and belonging”